Subscribe to discover Om’s fresh perspectives on the present and future.

Om Malik is a San Francisco based writer, photographer and investor. Read More

My recent rumination about “The Greatest Invention Is…” triggered some thinking around my long-held beliefs about the duality of technology. It left me brooding over the weekend about the present and the future. I started going through my notes and came across two separate entries with my thoughts on “stuff” I had accumulated during my research and reading adventures. They helped connect a few dots.

“Optimism is a strategy for making a better future. Because unless you believe that the future can be better, you are unlikely to step up and take responsibility for making it so.” — Noam Chomsky

I think I flagged that quote because Chomsky is the last person I would have labeled as someone who leaned into future and progress. Under his quote, I had these questions spurred by his words:

And my answers.

It’s nothing if not all a moving target. It is about change. Eventually, the present becomes a future normal. The imagined future simply becomes reality. If you are a long-time reader, you know my personal disposition towards such thinking. And I noted as much in my second note.

I had written some thoughts around various snippets from Hind Swaraj, a book by Mahatma Gandhi, originally published over a century ago. He was writing about a future that is now all too present around us. He was addressing similar if not the same social injustices that are often discussed today. He was not writing about India. His was a critique of the entire West and what civilization was becoming as a result.

The upside of reading books from a century ago is that you can see how our lived history has panned out, and how much of what was an imagined future has become reality. Gandhi’s book is a good narrative tool. It is not about technology, but about society as it was changing due to the rise of new technologies. There is a strong parallel to our present. In a sense it gives us a hundred-year arc on the human condition.

As a society we are now imagining a future that is more abstract, more dystopian, and more full of anxiety. Gandhi and his peers might have felt the same over a century ago. Should we feel the sense of overwhelming anxiety and dystopian despondency, or should we take a “roll with it” approach?

The parallels in Gandhi’s book with today are shocking and amusing at the same time. What he fretted about feels so quaint, normal and routine now. His writing from a century ago only reinforces that we have an ever-changing idea of what is reality, what is a perceived future, and what eventually becomes the future.

With the hindsight of the near history, and if you squint, you can see our “smartphone present” in the description of the future Gandhi wrote about:

“It has been stated that, as men progress, they shall be able to travel in airships and reach any part of the world in a few hours. Men will not need the use of their hands and feet. They will press a button and have their clothing by their side. They will press another button and have their newspaper. A third, and a motor-car will be waiting for them.”

I use my phone to have my dry-cleaning picked up and dropped off. We can fly anywhere from anywhere in less than a day and make all the arrangements on our phones. News via the internet. Uber is nothing but a car on demand. Somewhere in his book, Gandhi notes that “Civilization seeks to increase bodily comforts, and it fails miserably even in doing so.”

Thanks to the gift of hindsight, I have a tough time reconciling with that logic. While it might not be true for all humankind, we have seen bodily comforts go up, through our ability to turn dead dinosaurs into things that can be used, or are useful, and are utterly pointless. Sure, we are killing the planet in the process — an irony not lost on me. We are becoming dinosaurs ourselves, hopefully to power some future Labubus.

The meta point is that now that we are indeed a button-pushing society, how long before this lack of friction starts to erode what could be described as human capacity? We will forget what it is like to do something ourselves. Just look at how we use our navigation systems as a crutch. It has already eroded our sense of direction, and the meaning of place. Location has been abstracted into the tiles of a map.

“Formerly men were made slaves under physical compulsion; now they are enslaved by the temptation of money and of the luxuries that money can buy,” Gandhi wrote.

What was described as “temptation” a century ago is now bare necessity. Gig workers are not driving for comfort, but for rent. It is estimated that there are over a billion gig workers worldwide. Most of them combine gig work with other jobs because neither alone covers the bills. The past is now reality, just in a different form.

As I re-read my own notes and highlights from Hind Swaraj, a few other important bits stood out. “There are now diseases of which people never dreamed before, and an army of doctors is engaged in finding out their cures, and so hospitals have increased,” he wrote.

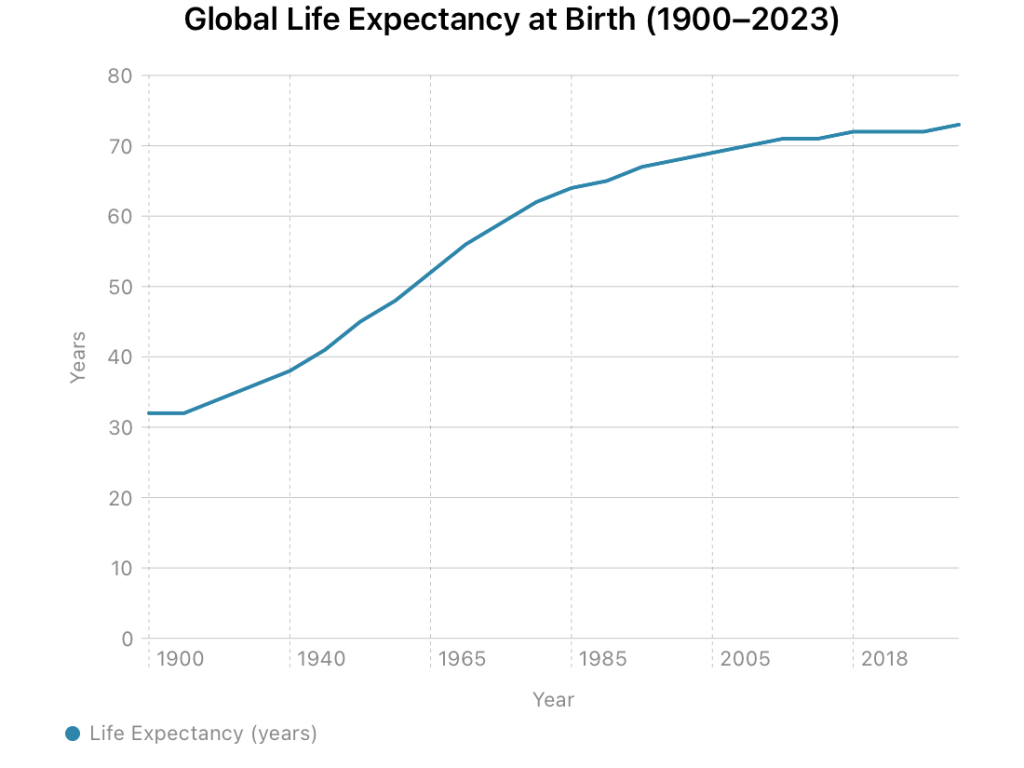

At that time, what he wrote probably felt like a futile exercise. But was it? In 1900, the average human life expectancy was thirty-two years. Today it’s seventy-three. We more than doubled it in a century. Finding cures is progress. That’s real and measurable.

But of course, with change come new diseases of modernity. Diabetes, heart disease, and growing incidents of cancer. The number of adults with diabetes worldwide quadrupled from 108 million in 1980 to over 580 million today. We engineered a food system for convenience and then built a trillion-dollar pharmaceutical industry to manage the consequences. Ozempic is a perfect example of a technology fix for the damage wrought by the system we built for comfort.

Progress? Dystopia? I’m not sure. The duality of technology is always there. As Robert Louis Stevenson wrote of Jekyll and Hyde, we are “radically both.”

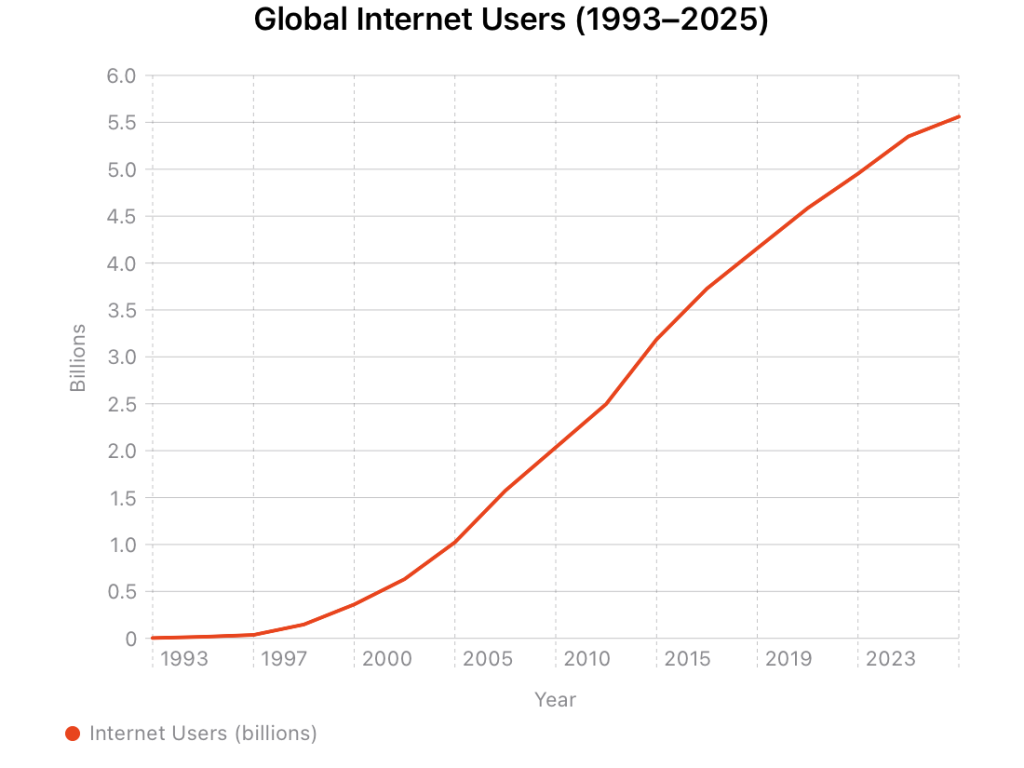

Of course, nothing showcases the excesses of technology like communication systems. Always has. From carrier pigeons to mail trains to the Internet, communication and the ability to communicate have been disruptive and disturbing.

“Formerly special messengers were required and much expense was incurred in order to send letters; today anyone can abuse his fellow by means of a letter for one penny,” he wrote, adding, “True, at the same cost, one can send one’s thanks also.”

I bet even he didn’t think we would end up with Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram. Great tools for communication and amusement. But also tools for selling a story, not simply telling one.

As a society, now, we are staring at a hazy new future. We are living in the petri dish of tomorrow. People talk about AI as jobs lost and “existential risk.” Our challenge is a lot less complicated. Passivity. Not the headline stuff, but quiet subjugation. Convenience, subsuming us, one bit at a time.

Gmail finishes your sentences. Spotify tells you what to listen to. Amazon reorders your toothpaste. Small things. Tiny bits of surrender in the name of comfort. You didn’t choose the words, the song, the brand. The system became the arbiter. Passivity by a thousand defaults. No longer Gandhi’s button-pushers — something less than that.

And now here comes AI with its agents and assistants. Every startup says they will book your travel, manage your calendar, draft your emails, handle your shopping. You won’t even need to lift a finger. Just let the system learn your patterns and act on your behalf. That’s not a tool. It’s a replacement for choice and choosing. Passivity for the next century. We will call it progress. But is it progress, or is it dystopia?

Any conclusion we arrive at today is not relevant. Gandhi laid out his idea of the future of society with clarity. I can’t say if he was right or wrong about his warnings. As someone who is predisposed to looking at the future, I see it as progress. Not dystopia. Whether it’s progress or dystopia depends on where you stand.

Let me close with Chomsky’s words: “Unless you believe that the future can be better, you are unlikely to step up and take responsibility for making it so.” I think it will be better. I am sure someone a hundred years from now will crunch the numbers and let future versions of fellow humans know.

February 9, 2026. San Francisco

Two quotes inspired by your post today:

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.

One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.”

― F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack-Up

“Ford carried on counting quietly. This is about the most aggressive thing you can do to a computer, the equivalent of going up to a human being and saying ‘Blood…blood…blood…blood…'”

― Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy